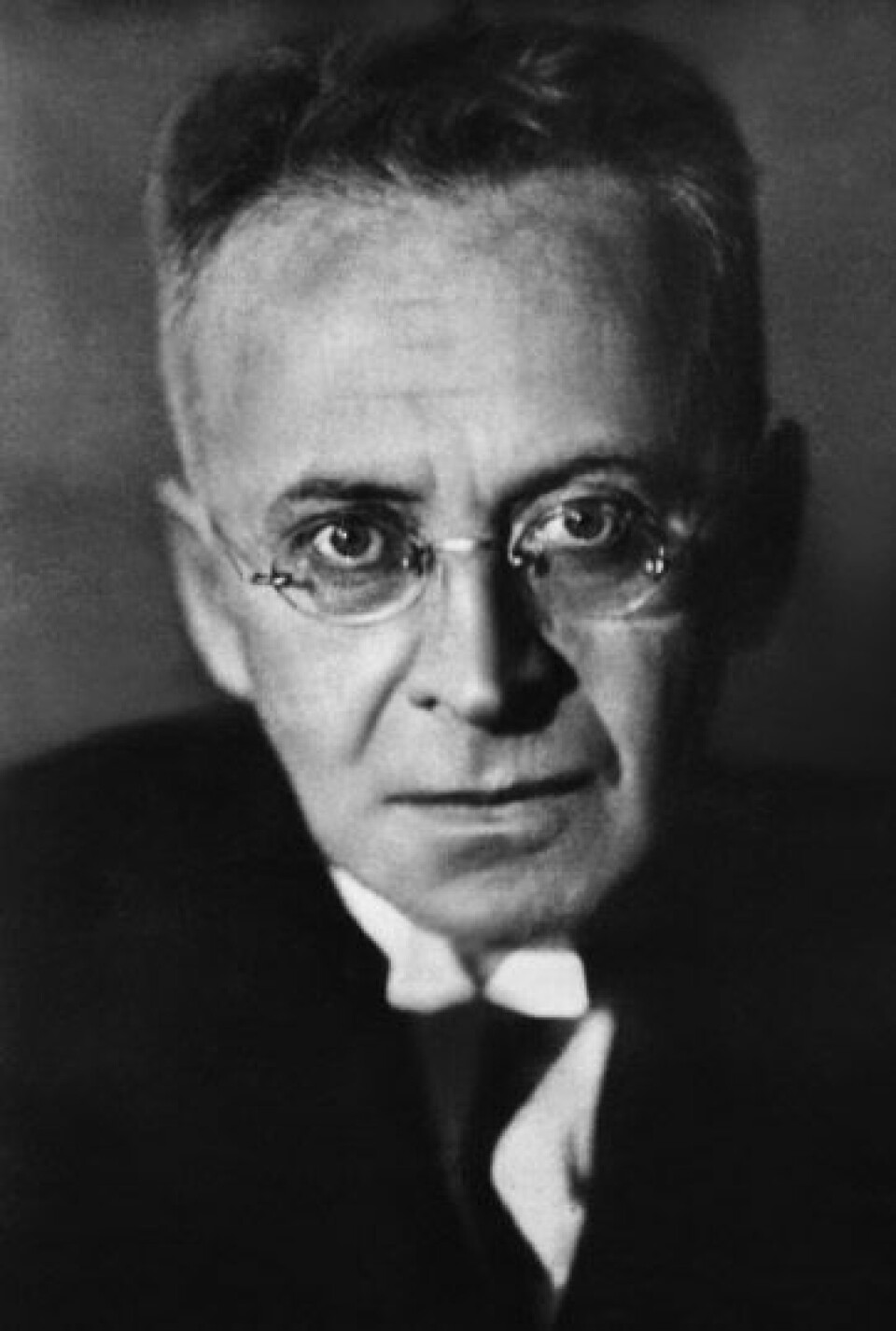

Jonathan Franzen: – Silicon Valley is profiting from the coronavirus

The internet makes us miss out on the chance to do some self-reckoning during the pandemic, says the American author.

Jonathan Franzen is still in his office in Santa Cruz, California when we reach him, even though he is finished with his day's work, according to his daily writing schedule. He is working on what he will later reveal to be his next book project, the measures and nature of which we will return to.

– It makes sense to talk to you right now, with the corona situation, because this is just like something that would happen in a Franzen novel, only worse.

– Yes, says Franzen, with something between a laugh and a sigh. There are many of these sounds during the interview.

Profits on the crisis

Jonathan Franzen was born in Western Springs, Illinois, in 1959. He published his first book in 1988, but his real breakthrough came with the novel The Corrections in 2001.

The novel follows a traditional American family. The values of two generations are in constant confrontation and adjustment as they try to find ways to improve their situation in a society that also is hit by the impenetrable laws of finance.

The novels that followed, Freedom (2010) and Purity (2014), also became best sellers. These are books you can pick up at the airport, but have been praised by critics as modern classics.

– Does the corona crisis reveal something about the modern American society that you have also investigated in your novels?

– Yes, I have actually been saying no to many interview requests to speak about the crisis. People want me to write something, and I say no. The reason is that it seems too early to know what is really going on. The whole condition now is uncertainty. I could describe the various levels of uncertainty – about the economy, the virus, the political consequences of all this, but I would just be doing what everyone else is already doing.

Franzen claims he is not a very good predictor of the future. He does however admit that he has been right about a few things in the past.

– I think I was right about social media very early on. I think, even earlier, I was right about what a lie it was that the internet was going to bring about world peace and universal friendship. So, you know, sometimes I get things right, but in this case, it is just too early to say. I would say the fear that has been preoccupying me is that this is completely playing into the hands of Silicon Valley and the tech industry.

And with that we seem to be tapping into something.

According to Franzen, there is nothing the tech industry in Silicon Valley would like more than for people to never leave their house and do nothing all day but look into their screens.

– They would like nothing more than to destroy every local business and make everything purchasable only on the internet. Given my long-time animosity to the totalitarian tendencies of Silicon Valley, I would say that it has been the darkest thing for me. We try very hard in Santa Cruz to support our local businesses. The local bookshop is doing well because it has so many loyal customers. The doors are closed but they are still doing curbside pickups and mailing books to people. They've had a better month than they normally would because people have been so supportive, but that’s unusual. I live in a place that is very focused on supporting the community. I do worry about the larger American landscape in that regard.

The thing that is so unbearably, wonderfully moving to me is that it's not just time that heals the wound, it is also nature.

Jonathan Franzen

– We are talking about the possibility of a new economic depression, but are some profiting from this?

– Definitely. The stock market in the US went down very quickly and strongly in the beginning of the crisis, but it has come back up, you know, very nicely. I do think we are in for a depression, or at least a very severe and sustained recession. But people still have money and they still need to spend it.

Franzen laughs his sad laugh.

– I think certain parties are going to do very well from this.

To miss out on oneself

– Where would we be right now if we didn’t have the possibility to keep running businesses from home?

– I don’t think the internet is all bad, I think it has been very useful as a business tool. The ability to send documents and have group meetings is all very good. At the same time, if you imagine that this was happening in a world 30 years ago in which we only had telephones, it’s possible that people would be thrown more back on themselves. It’s possible to imagine more books being read.

It is a kind of 'Waiting for Godot isolation' that Franzen thinks we are missing out on, and with that a chance for people to go into some sort of reckoning with themselves.

– I think the prevalence of screens allows a way out of that. And that has come to be, largely, the function of the internet, and in particular of social media. It has been a kind of distraction, a drug with which you treat the feeling of isolation rather than having to deal with your own aloneness. So yes, obviously, I am very happy for my friends who are still able to work from home. But in a larger scheme, is it a good thing? I am not so sure.

Two types of progress

The faith and doubt concerning the possibility of progress keeps returning in American literature, from Herman Melville's Moby Dick and F.Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby to contemporary writers such as Franzen himself. This is something we have been wanting to talk to him about.

– Is there any way around the idea of progress?

Heavy sigh from Franzen.

– Well, that’s a large and somewhat abstract question. I think my first conscious work with the question of progress came with my reading of Karl Kraus (1874 - 1936). One of my stranger little books is called The Kraus Project, and consists of translations I have done of some of his essays, with very lengthy annotations. Karl Kraus was active exactly when the rhetoric of progress had swept over the western world, Franzen explains. It was about a belief that technology was going to make the world a better place, and that science was going to solve all our problems.

– Flash forward a hundred years, and we have people in the technology world thinking that we are going to solve the problem of death. People won’t ever have to die. You know, crazy stuff like that.

Literature is paying attention to the cost.

Jonathan Franzen

– Well, that’s a large and somewhat abstract question. I think my first conscious work with the question of progress came with my reading of Karl Kraus (1874 - 1936). One of my stranger little books is called The Kraus Project, and consists of translations I have done of some of his essays, with very lengthy annotations.

Karl Kraus was active exactly when the rhetoric of progress had swept over the western world, Franzen explains. It was about a belief that technology was going to make the world a better place, and that science was going to solve all our problems.

– Flash forward a hundred years, and we have people in the technology world thinking that we are going to solve the problem of death. People won’t ever have to die. You know, crazy stuff like that.

Kraus responded to this idea by making a distinction between two kinds of progress, Franzen continues. On the one hand, there is technological progress, on the other hand, there is moral progress.

– If you go back to the utopian rhetoric of the early nineties and mid-nineties coming out of Silicon Valley, they saw that there was going to be a tremendous explosion in the potential of what technology could do.

In their – I think in their cynicism, but you could also say, in their innocence – they conflated technological progress with moral progress. They said that If we can get everyone in constant communication with everyone all over the world, then surely the world will be a better place.

The way Franzen sees it, this idea persisted up until November 2016 in the United States of America.

– Then we finally said, well, you know what? Technology has gotten a lot better, but people have not gotten better at all. So this is a long way of answering your question without going into specific examples from the body of American literature. But I do think that literature has its roots in tragedy and comedy. And both tragedy and comedy are about the way things don’t change.

We can subscribe to the new religion of technology, Franzen thinks, but that is not going to save us from what is really going on: a world of death, of people doing bad things, and of completely unresolvable conflicts in one’s own self. These are all things that do not change, and what literature has always tapped into.

– I did, for whatever reason absorb this pretty early, and it continues to inform my writing, Franzen says, and adds:

– Then in the last 10 to 20 years, it has become increasingly clear that we are not going to stop catastrophic climate change, and by that it has taken on a whole extra dimension. Things have gotten better in many ways. There are fewer starving people in the world. Millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. All these good things are happening, but it has come with a cost. Again, that’s where I am with literature. Literature is paying attention to the cost.

Nature heals the wound

In The Corrections, Franzen lets the young man Chip throw the books of his beloved neo-Marxist thinkers out of his shelves, but he is not able to part from his Arden-Shakespeare collection, while Freedom opens with an epigraph, a quotation from one of William Shakespare's late plays, The Winter's Tale.

– How does the quotation from the Winter’s Tale relate to what you said about things that don’t change?

– You know, Shakespeare wrote all his great tragedies, and the thing his tragedies have in common is that events move quickly. If Othello would have just had a couple of days to gather a little more information, he would have realized that he was being tricked by Iago. The terrible things happen because there is no time.

Later on, after writing his great tragedies, Shakespeare became, like Franzen calls it, more of a novelist.

– The four late plays of Shakespeare, including The Winter's Tale, are called romances. And of course, in many European languages, the word romance is basically the word for novel (which is also the case with the Norwegian word roman. Ed).

What is striking to Franzen about these romances, is that they follow a pattern: a personal tragedy occurs, the badness of people causes terrible things to happen, and then time goes by.

– The thing that is so unbearably, wonderfully moving to me about The Winter’s Tale, is that it’s not just time that heals the wound, it is also nature.

Shakespeare moves his play into the natural process of regeneration, Franzen says. It is like coming back 15 years later to the place where a terrible forest fire has burned everything, and finding it full of life. He maps the natural process of regeneration into a kind of moral scheme where forgiveness and reconciliation is possible.

– To me it’s an intensely religious experience, reading or watching that play, because, you know, that’s where hope lies, in the possibility of forgiveness.

Franzen has also found himself moving in this direction as a novelist. Since his first two books take place over a period of about six months, he has become increasingly interested in longer timeframes.

– So one of the reasons I wanted to call out the name of The Winter's Tale in that epigraph, was to point toward what an inspiration Shakespeare is in that regard. He turned into a novelist when he started stretching out the time.

– Some people are talking about the corona crisis as a chance to do better, and to make changes for the climate. Is it possible to adapt these notions of the nature of forgiveness from the personal sphere to the social situation?

– Here is my concern: In a very practical way, we are not allowed to leave our houses. You know, we can still take a walk in the neighborhood, but in the last five days in Santa Cruz, they have shut down every trail, park and beach. They will open them back up, but the longer we stay inside, the more we move in the direction of seeing everything on a screen.

Franzen’s feeling has long been that the best way to get people to care about the natural world is to bring them into it. That way they can see that there is something to love there. That way you are not only motivated by a selfish fear of what is going to happen to you, but you will positively care about something you want to save.

– So, I don’t know. I don’t know if this is a good way to change things, to have everyone locked up with their screen.

I initially envisioned it as one novel. My last novel.

Jonathan Franzen

The great American novel

– You let 9/11 play a great part in Freedom...

– Did I? It’s just a tiny little bit, it’s like two pages!

– Well, Joey wouldn’t do what he does (some shady business selling parts to military vehicles on the American side in Iraq. Ed) if it wasn’t for 9/11, would he?

– That’s true. But I was very focused on not writing a 9/11-novel. Because, Good Lord, we had about hundred times too much attention to 9/11, and then the idea that you were supposed to write a novel about it? I can’t imagine it, it would be the last thing I would do.

– Well, because my next question was going to be: Will you write the great novel about life in America after Trump?

Franzen politely asks for two seconds to get a sip of water.

– I don’t do treatments of public events particularly, he says. – If I do, I try not to call attention to it. The rallying part for me is something Don DeLillo once said to me: The writer leads, he doesn’t follow. I don’t want to be the novelist tracing along with my interpretations of things the media have already covered to death. That’s just not interesting to me. I am paying attention to things it seems to me that people aren’t paying enough attention to.

It is at this point Franzen comes to talk about his new book project.

– I am nearly done with the first volume of a three volume novel I set out to write. I have been writing for two years. Across the room I can see some paragraphs from the third-to-last chapter. I initially envisioned it as one novel. My last novel. But then it turned out I had more to work with then I’d realized.

Franzen reveals that the first novel goes no further in time than 1975, but that most of it is set in 1971 and 1972.

– It is written in the time of Trump, so I think that if I looked carefully, I could see the signs of that. And of course, this is only volume one, so it will eventually get to the present day and probably beyond the present day by when I’m done. But no, there is nothing…

– There are hundreds and hundreds of good writers, smart people whose job it is to pay attention to this stuff and write about it every day. We don’t need me coming along afterwards. So, it will be there, but not, I hope, in the way you would expect.

Photo: Mary Altaffer, NTB Scanpix